“Oh to be a fly on the wall…” You could be when Robert Zemeckis’ Here comes out.

Based on Richard McGuire’s 2014 graphic novel of the same name, Here only has one point of view. The camera is in one position. Think of the camera — and therefore the point of view — as that of the fly: an immortal, stationary fly.

Zemeckis told Vanity Fair in an exclusive first look, “The single perspective never changes, but everything around it does.”

“It’s actually never been done before. There are similar scenes in very early silent movies, before the language of montage was invented. But other that, yeah, it was a risky venture,” he added.

Here is a Forrest Gump Reunion

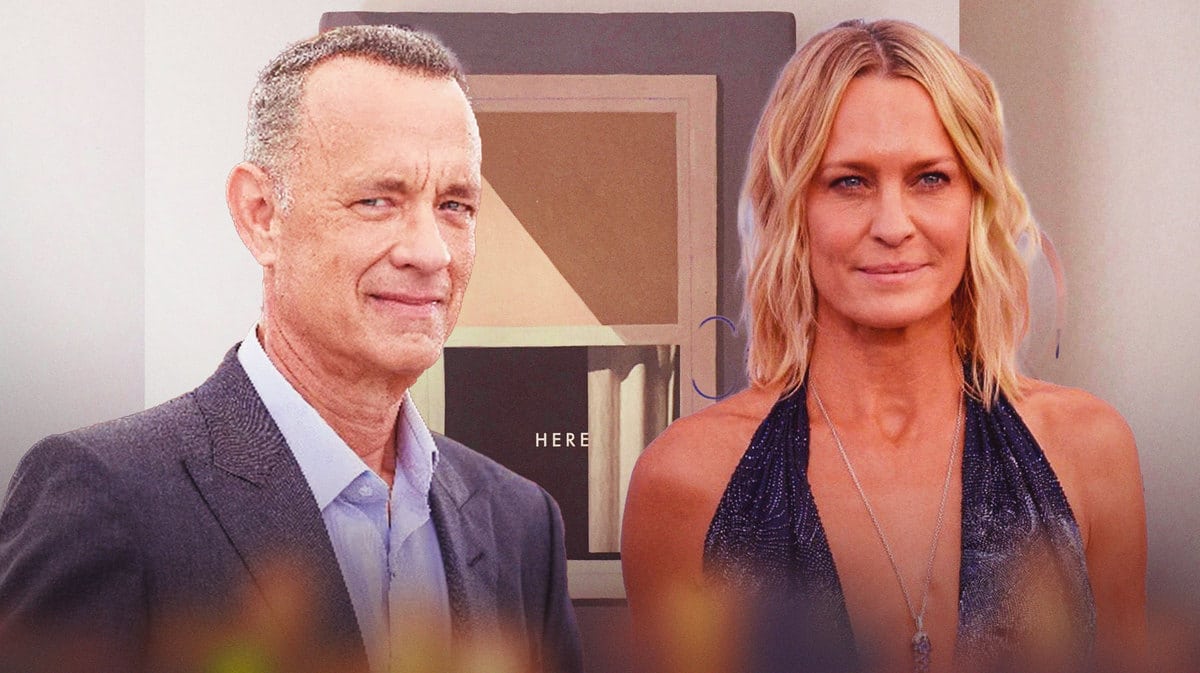

The movie reunites the director with his Forrest Gump stars, Tom Hanks and Robin Wright, and co-writer Eric Roth.

While Here’s unusual single-camera POV hasn’t been shared before now, those who’s read the graphic novel are aware of it. However, translating this to a 104-minute film is risky, as Zemeckis said.

“That’s the excitement of it. What passes by this view of the universe? I think it’s an interesting way to do a meditation on morality. It taps into the universal theme that everything passes,” he explained.

Going back to the single point-of-view, while that doesn’t change, the actors do. More than that, they age. Hanks plays Richard, a baby boomer. In the film, he is sometimes 67 years old, but he also plays his younger selves, thanks to makeup and digital de-aging. The actor also plays himself in his late 80s, and then goes back to a young man in the 1960s — think Hanks in Bosom Buddies in the ’80s.

The same goes for Wright. The audience will first meet her Margaret as Richard does in their late teenage years as his girlfriend, then his wife and the mother of their children. They age and de-age together as they traverse the decades.

The 72-year-old Zemeckis said, “Eric and I wrote our generation.”

The filmmaker isn’t a newbie when it comes to de-aging techniques. In fact, his 2004 holiday film The Polar Express was the first to try it out. He refined his techniques three years later with Beowulf and then again in 2009’s A Christmas Carol.

De-aging and the “uncanny valley”

However, this can and has been tricky. When The Polar Express came out, many people described feeling a little off watching the characters, often referencing the “uncanny valley.” The term was first introduced by a Japanese robotics professor, Masahiro Mori, in 1970. In Japanese, it’s 不気味の谷, bukimi no tani genshō. Literally translated, it means uncanny valley phenomenon. In 1978, Jasia Reichardt shortened it to just “uncanny valley” in her 1978 book Robots: Fact, Fiction, and Prediction.

The phrase refers to a psychological and aesthetic relation between how an object resembles a human being and how humans react to the resemblance. This is commonly used when discussing robots, 3D computer animations and lifelike dolls. The reaction is usually unsettling. It’s like the human hindbrain sees it as a human face, much like its own, but knowing that it isn’t.

Other films since have used de-aging techniques such as Martin Scorsese’s 2019 Netflix film, The Irishman, which erased decades off its stars Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci’s faces. However, critics weren’t convinced; they still maintained that they didn’t so much look like young De Niro and Pesci, but still the old guys albeit with young faces. Is that confusing?

But technology has advanced since then, and Zemeckis used those exact advances to his advantage in Here.

“I’ve always been, for some reason, labeled as this visual effects guy. But those were always there to serve as the character arc. There’s always been a restlessness in trying. I’ve always thought that our job as filmmakers is to show the audience things that they don’t see in real life,” he explained.

So how does it work in Here?

“It only works because the performances are so good. Both Tom and Robin understood instantly that, ‘Okay, we have to go back and channel what we were like 50 years ago or 40 years ago, and we have to bring that energy, that kind of posture, and even raise our voices higher. That kind of thing,” Zemeckis elaborated.

Maybe that is the key to making de-aging work: it can’t just be the face that’s young. It has to be the performance as well. Remember Robert Downey Jr.’s young Tony Stark in 2016’s Captain America: Civil War? Granted, I’ve always seen Tony as this enfant terrible. I didn’t expect that his younger self would be any different. Worse, maybe, but not all that different. But I think what convinced me is how, in that scene with his parents, his face showed the kind of hurt someone in their 20s don’t necessarily think to mask. The older Tony certainly did.

We’ll go back to de-aging later. Let’s go back to my immortal and stationary fly’s point of view. In Here, time passes by this one shot, the living room. The filmmaker uses gradual transition to mark the passage of time instead of jumps. For example, to transition from the ’60s to the ’30s, the television beside the fireplace will morph into a radio instead. The rest of the room then fades in to complete the ’30s look.

The camera never moves, never zooms

“Instead of cutting to the next image in the full screen, we’re [easing] into the next scene, bringing us into the next moment in a way that allows us to actually overlap stories,” the director said.

It’s a lot like watching a stage play on film, only instead of being able to see the set change through movers removing and adding furniture, you don’t see the stage hands.

As Zemeckis elaborated, “When you’re watching something on the stage, you are the editor and the filmmaker. You decide, ‘Am I going to watch that character or am I going to look over here and see that guy who’s sitting on the sofa?’ What we do with the panels is we guide the audience to what we want them to see.”

Still on theme of stage, the director sets the tone for Here the same way as Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, but in just one room. Hanks’ Richard is overwhelmed by his overbearing father Al (Paul Bettany), and his mother Rose (Kelly Reilly) finds her personality submerged as well . Since he grew up in this kind of environment, Richard clashes with his wife Margaret when she wants to pursue her own dreams.

However, Richard is also a child of the ’50s who wanted to become an artist and had to choose his responsibilities as a husband in the ’70s and a father in the ’80s. As time passes by and the millennium enters, he realizes how much time has passed by. Margaret, on the other hand, has been all too aware of the passage of time and urges him to finally pursue his dreams.

Zemeckis noted that the film encapsulates physically in a tight space that everything changes and there’s no other choice but to accept it.

“Where we get in trouble is when we resist that reality of life, and then we get dug-in and miss out on opportunities,” he added.

Hanks, Wright, Bettany and Reilly are joined by Michelle Dockery and Gwilym Lee as the house’s first resident at the turn of the 20th century, David Fynn and Ophelia Lovibond in the ’20s, Nicholas Pinnock and Nikki Amuka-Bird move right after Hanks and Wright move out, along with their housekeeper played by Anya Marco Harris. The last couple live in the present time.

I did say we’re going to go back to the de-aging technique, right? Well, it seems that only Hanks and Wright will be subject to that. Their family is the focal point of the story so we see them from their youth to their old age. In VF’s first look, I don’t really feel an “uncanny valley” type of way. If I didn’t know any better, I would say the effects only airbrushed the lines off their faces. But there’s something a little off with Hanks’ arms. I can’t pinpoint what it is. Maybe it’s because it’s a still photo and it will look different when we finally get the trailer and we see them in action.

Time, as is always at the center of Here, will tell.