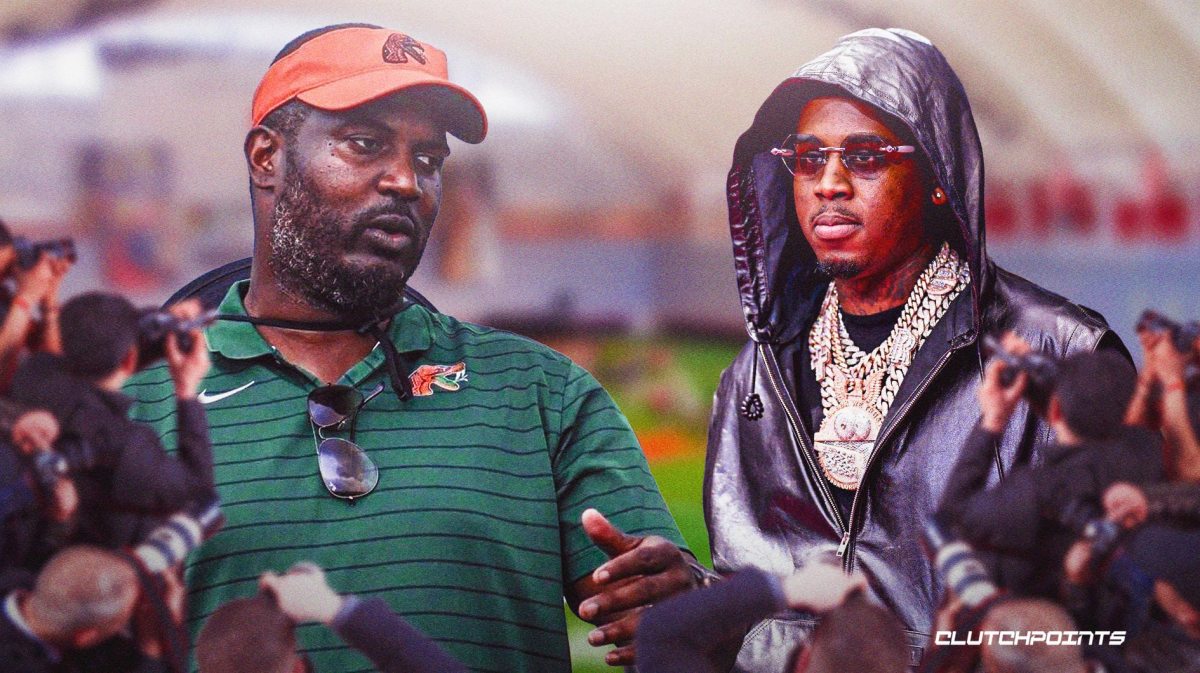

Recently, the HBCU community was led to shock when Tallahassee-based rapper Boston Richey released the music video for his song “Send A Blitz”. The video was largely filmed at the Galimore-Powell Field House on Florida A&M’s campus, utilized by the Rattler football team. In the video, you can see FAMU trademarks and sponsor logos such as Nike. Boston Richey and the participants in the videos at several points have on football helmets and Boston himself sports an orange FAMU polo. A few hours after the release of the video, FAMU Head Football coach Willie Simmons released a statement condemning the filming of the video on campus and announcing that all football activities for the team were suspended until further notice.

The suspension has since been lifted and FAMU is set to begin preparation for the new season on August 4th. The investigation into the incident, led by the Office of Compliance & Ethics, is still ongoing.

— Tiffani-Dawn (@Tiffani_Sykes) July 24, 2023

Many took to social media to express their opinions on the matter. Many spoke in support of the actions of FAMU administrators, agreeing that the video shouldn’t have been filmed on campus without prior authorization by the university and that it is indeed a bad look for the school. But, I saw a lot of people that criticized Coach Simmons and FAMU for their actions. The critics called FAMU’s actions hypocritical, citing the fact that FAMU has a Homecoming concert every year featuring artists that have similar lyrics to what Boston Richey raps in “Send A Blitz”. They also argue that the video was good for the school, a thought process in line with the infamous saying “All attention is good attention.” The reasoning behind these comments is wrong. And, to be clear, Boston Richey was wrong to shoot his “Send A Blitz” video at FAMU.

https://youtu.be/XcOx7DZanNw

There’s a rational way to look at this that supersedes a respectability politics argument and the thoughts of those playing Monday Morning PR professionals. There isn’t inherently a problem with rap itself being tied to HBCUs. In the 50-year history of Hip-Hop, the genre has always intersected with HBCUs. Some of the rappers and producers attended our institutions as students such as Common (FAMU), 2 Chainz (Alabama State), Rick Ross (Albany State) and even super producers like Mr. Hanky (Southern) and Metro Boomin’ (Morehouse). Marching bands such as FAMU’s Marching 100 play popular hip-hop songs every Saturday in the Fall. And yes, students demand that the most popular rappers of the moment make an appearance at their Homecoming concert and often grade the quality of their homecoming by the status of the artist that performs.

However, those are separate topics. “Send A Blitz” is a unique issue that had to be handled differently. The music video was shot on campus without prior authorization. The statements by FAMU and Coach Simmons explicitly say that, citing the branding and licensing issues that the filming of the video poses. But the biggest problem is the lyrics themselves. “Send A Blitz” is a song that features violent, misogynistic lyrics. Florida A&M, an institution that brands itself as the “College Of Love And Charity” clearly wouldn’t endorse lyrics that call women out of their names and talk about violence, guns and explicit sexual acts. This isn’t a sanctimonious take, it’s just common sense.

Common sense seems to be absent in many opinions about this situation though. Not only are people looking past the two aforementioned issues that caused FAMU officials to release statements condemning the video, but they are also even saying that the “Send A Blitz” video is good promotion for FAMU. Do people really think that Florida A&M, the number one public HBCU in America as ranked by U.S. News & World Report, needs a music video shot on campus to place attention on the institution? A university that goes viral all the time and made national news for positive content featuring Rattler cheerleader Nailah Clarington as recently as late March needs clout off of Boston Richey’s name? At some point we have to make our arguments make sense.

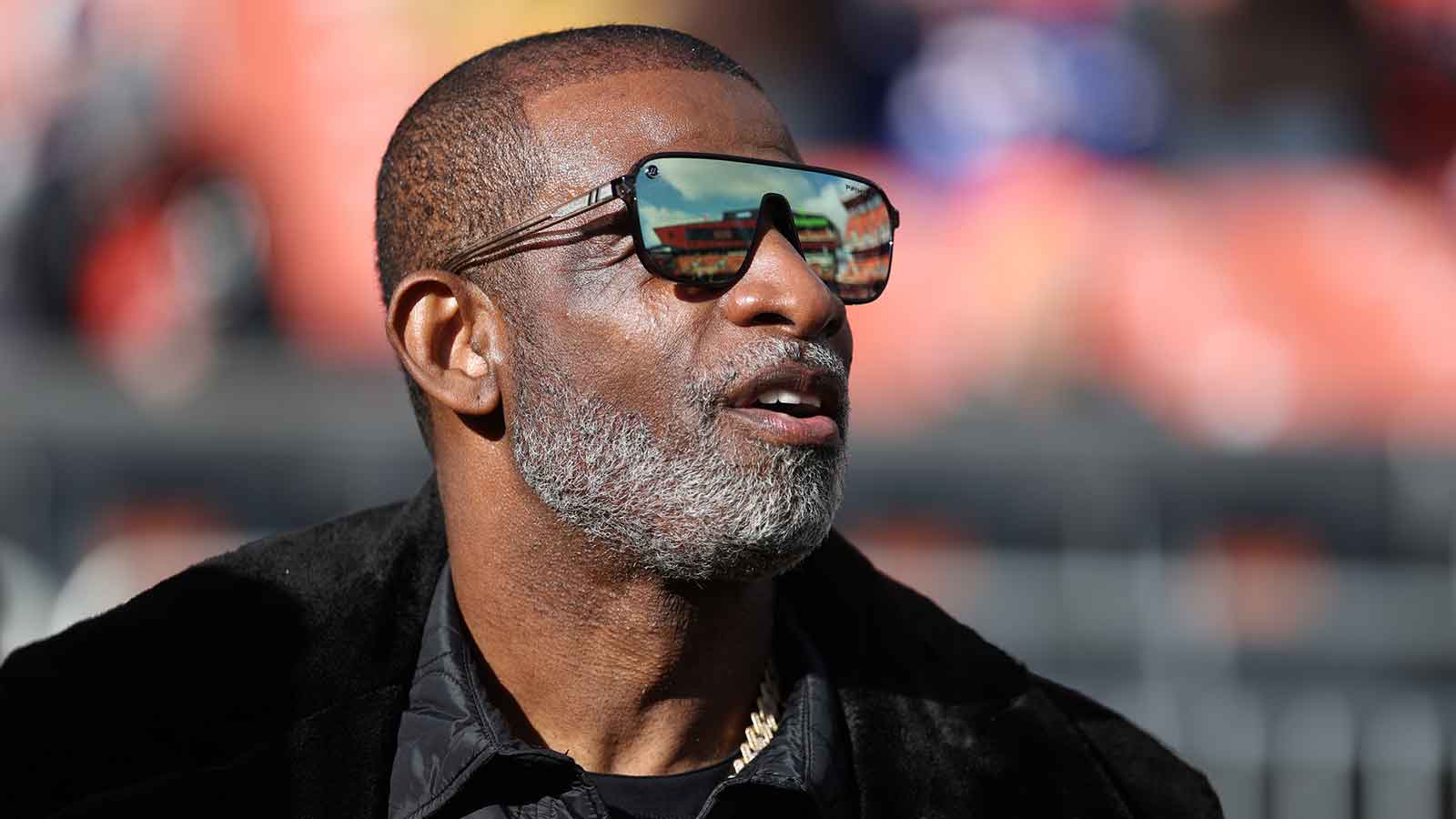

View this post on Instagram

But the point goes even deeper than that. There’s this notion that people aren’t aware of HBCUs and Boston Richey, who is a prominent up-and-coming rapper, can bring awareness to a new generation. There’s a thought that music videos shot on campus can make FAMU look “cool”. Now, forgive me because I was not a football or basketball recruit, but I’d be looking at factors other than what rapper wants to shout out FAMU if I was picking out who I wanted to commit to. FAMU’s football bonafides are solid. They won the first FCS Championship ever in 1978 and are the only HBCU to do so. They produced two NFL Hall-Of-Famers in Bob Hayes and Ken Riley and dozens of other NFL Players.

If you don’t care about history, we can talk about what’s happening right now. FAMU has a multi-year partnership with Nike and LeBron James, the first HBCU to have a deal for LeBron’s apparel line. They just had a docu-series based around the football team on ESPN+, executive produced by Chris Paul. FAMU has three HBCU players in the NFL right now with Markeese Bell, Isaiah Land and Xavier Smith. Why wouldn’t FAMU be an option for any recruit? What more do they have to do to fit the widely believed definition of “publicity”?

Back to the “Send A Blitz” video. If Boston Richey made a song “Send A Blitz” that was similar to Jay Rock’s “Win”, Nelly’s “Heart Of A Champion” or Florida native Ace Hood’s “Hustle Hard” we wouldn’t be having this discourse. I even believe that the situation would’ve been handled in a more private matter if the song was a more traditional hype sports song. Maybe Boston Richey and his team would’ve been hit with a warning and Coach Simmons and FAMU’s communications department would have spoken to him and his management team. But the problem that arises, once again, is that the video was shot on campus without prior authorization by university officials and the lyrics were reprehensible.

FAMU Administration and officials handled the situation with tact by hopping in front of the controversy immediately. If they didn’t, concerned alumni, stakeholders and corporate partners would’ve publicly and privately called for action. Colleges are just as much a business as they are educational institutions. They have the right to decide what’s appropriate for their brand. They weren’t acting in hypocrisy or righteous indignation. They were acting in the interest of their institution. And if that can’t be understood, there’s nothing more that needs to be said.