Martin Scorsese's The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon have a “Grim Reaper”: Frédéric Yonnet.

The acclaimed harmonicist has played with the likes of Stevie Wonder, John Legend, Dave Chappelle, Quincy Jones, and Prince throughout his career. He has also recorded with the Jonas Brothers.

But when it comes to his film/TV work, he has worked on two Scorsese pictures, The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon. Working closely with the late Robbie Robertson, Yonnet infused his harmonica into these two scores. The two projects are very different thematically, but both utilize eery ambiance.

In The Irishman, Yonnet is like the film's “Grim Reaper” — his words, not mine. He signified the trouble that was going to appear on screen. If someone was going to get whacked, chances are, Yonnet's harmonica can be heard. In Killers of the Flower Moon, his harmonica represents greed.

This is one of the things Yonnet, a Washington D.C. resident, discussed. It was love that brought Yonnet from Paris to D.C., and despite the awful traffic — which he called a “vacation” in comparison to the traffic in Paris — his surging career likely also played a part in that as well.

He will be playing four special shows at the Carlyle Room in Washington, D.C. in December. On December 1, Yonnet will be playing a show at 7 p.m. and 9:30 p.m. local time, and he will play shows at 6 p.m. and 8:30 p.m the following night. Tickets go on sale Monday, October 30. For more information, check out their website.

ClutchPoints spoke to Yonnet about what the harmonica means in the Scorsese films, the origins of the instrument, and the late Robbie Robertson. Yonnet also responds to a claim made by U2's Bono at a recent Sphere show about the harmonica and discusses his friendship with Ed Sheeran.

Frédéric Yonnet-Killers of the Flower Moon interview

ClutchPoints: Killers of the Flower Moon is your second or third time working with the late composer Robbie Robertson. Can you talk to me about how you two built that rapport?

Frédéric Yonnet: So the process was very interesting and unusual for me. Usually, when you walk on a movie, you work based on images. But here, it was based on a conversation he and Martin Scorsese had in the past.

They've done numerous films together, so they already had a formula and a friendship — they were in college together.For The Irishman, he gave me three anchor points. He said, “Be sneaky, sexy, and, unexpected.”

Those were the three directions, the three emotions, the three feelings I needed to stay focused on. The result was interesting because they had given me some blueprints, some MP3 [files] of what they wanted to hear, and the melody was written on music charts.

So I delivered what they wanted on paper, but then after a while, they started really getting familiar with my sound and the way I morph the notes of the harmonica [in], and they basically gave me a blank canvas to do whatever I wanted — at least in the way I interpreted the melodies and to interpret it more in the way I was hearing it. And those were the takes they kept for the score.

CP: The harmonica is a cool instrument. I was just in Vegas to go see U2 at the Sphere, and one of the things that made me laugh is after the song “Desire,” Bono joked about the harmonica that it's a “very American instrument.” I'd love to hear your thoughts on that.

FY: It's part of the Americana sound, definitely. Let's go back. The history of the harmonica is much older than the history of America [smiles].

The free-reed instrument, which is the little blade that vibrates and creates the sound of the harmonica. We have 20 free-reeds in the harmonica I play. The free-reed is actually a Chinese invention. It was created in an instrument called the sheng, and it's a bamboo flute with several reeds inside. There [are] some openings on the side of the instrument and you can control which reed is going to vibrate by obstructing or opening the airflow through the instrument.

So fast forward to about 200 years ago, some German inventors decided to use that particular free-reed to incorporate it into some metal or some wood combs and put it on top and at the bottom of the combs. Those combs will then be embedded in a huge breathing contraption, and that's how the accordion was created.

And from there, they decided, Why don't we take those parts of the accordions [and] make them even smaller and allow each one of the players to actually just excel in one of those chambers. They created then this tiny piano tuner that fits in a packet. And they decided, Let's put more notes into this, and that's how the harmonica was created. The harmonica is actually the only instrument that allows you to play music while exhaling and breathing through.

CP: Any tips for beginners trying to learn the harmonica?

FY: There [are] plenty of lessons online that are great, but I think the best way to really fall in love with the instrument is try to play along with the music you actually listen to versus to the music the harmonica has been known to be incorporated in.

That's actually a follow-up answer to your question when you mentioned Bono because the harmonica being about 200 years old was extremely popular in folklore music in Germany, where it was from, and then it was incorporated in folklore music, wherever the accordion was embedded, because it was almost like an affordable accordion for a lot of people [smiles].

I think in the 1800s, the harmonica was incorporated in the Marines package, and that's what they call [it] the Marine Band. There's a diatonic harmonica called the Marine Band, it was included in the Marines package, and most of those military guys didn't know what to do with it. So they would give it away to people who wanted to be creative musically, but who did not necessarily have the means to buy an instrument.

And at the time, it was mostly Black folks in America. And from there, Black folks started into incorporating the harmonica into their music, blues and gospel. That's why the harmonica really fits well in those genres of music, it's because those genres grew along with its presence.

But the challenge is it grew and then it kind of, from my perspective, now this is me talking, it kind of stayed in those genres. It almost stopped being embedded in the evolution of music as we know it today. And that's why I figured that there's a great opportunity [to embed it into other genres], why not include the harmonica in some trap songs or some hip hop songs or some dance music?

And why not including the harmonica in some soundtracks?

CP: You said that the harmonica was trapped in one genre, so can you talk about imbuing it into something like Killers of the Flower Moon, which is so tonally different than anything Scorsese's done?

FY: So Scorsese loves highlighting the storyline of a movie with music. I find that he actually attributes a character to a musical voice in the soundtrack. In The Irishman, I was literally the sound of bad news [smiles]. Every time something bad was going to happen to a character on the screen, you could start hearing the harmonica show up. [I] was almost like the Grim Reaper, the martyr.

Similarly to what he did in The Irishman, in this one, Killers of the Flower Moon, I think the harmonica is the sound of greed. Every time you feel greed creeping in the back of the mind of any of the characters, boom, you hear that plucking upright bass and you hear the harmonica.

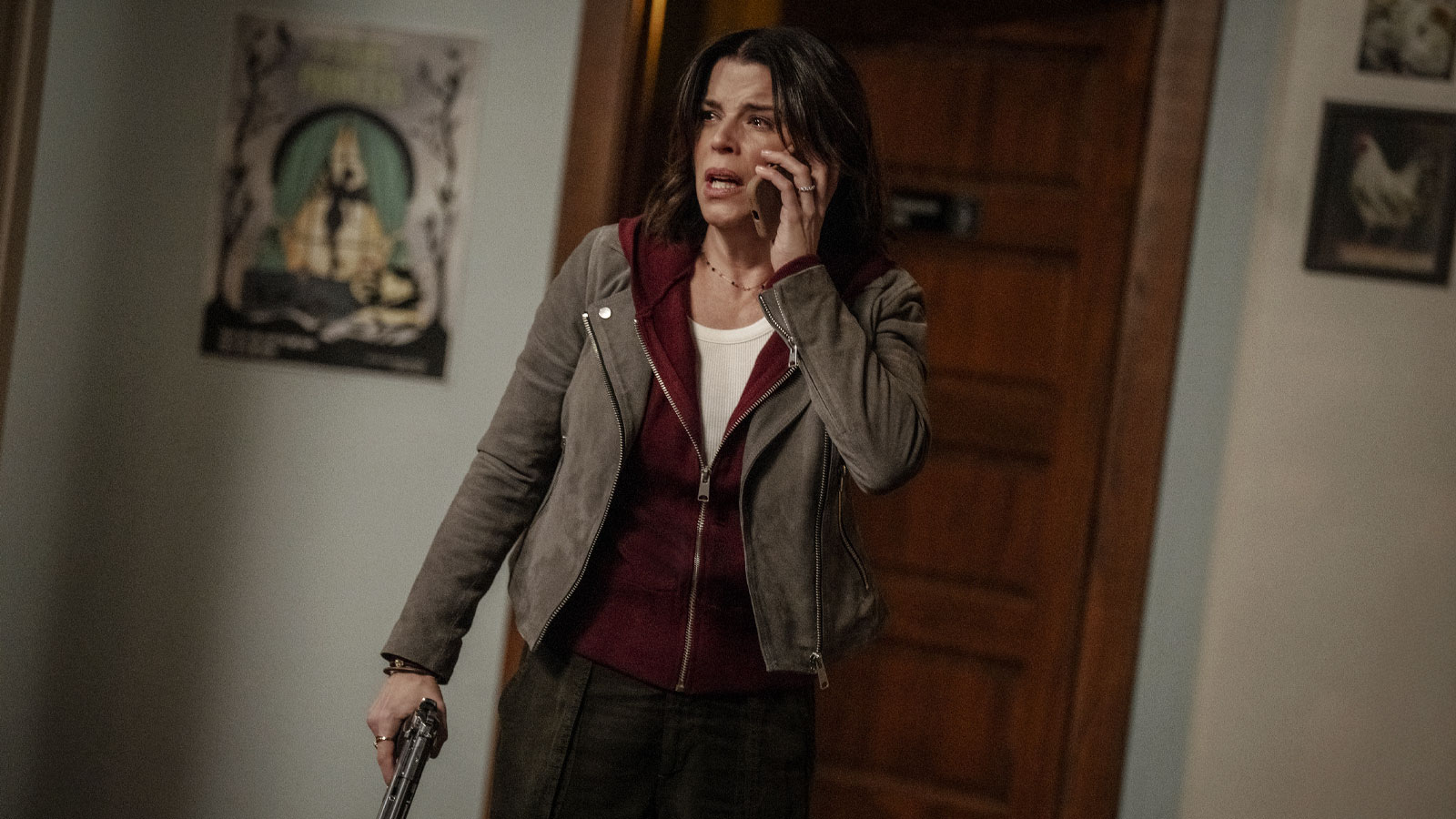

My harmonica starts to come in and out of the soundtrack and it becomes more and more present. At some parts of the film, it's actually extremely uncomfortable because it's very well tied in with some gut-wrenching emotions that the lead actress (Lily Gladstone) is delivering to the screen.

CP: The Irishman is one of my favorite movies. I absolutely adore that one, and now I have to go back and watch it back to hear the harmonica. Is that something that you have done with other films, or is that something you've done exclusively with Scorsese in those movies?

FY: I think it's really something that's particular to Scorsese. The idea of giving a role and a character to a particular lead instrument, that is something that he is extremely good at.

And he's so good at it that you and I didn't even notice it. I mean, I probably wouldn't have noticed it if I [wasn't] the performer. But it does have an impact because of the way the sound and the emotions are tied together. I know there's a particular scene in Killers of the Flower Moon, where [it] really creates a level of discomfort that makes you relate to what the actress is experiencing in that particular moment.

CP: You said Scorsese attributes an instrument to the characters, right? There's Lily Gladstone, Robert De Niro, and Leonardo DiCaprio's characters. Do you know what instruments each of them would be represented by?

FY: Oh, no, no. It's on a broader scale than this, from my perspective. Like I said earlier, the harmonica is the sound of greed. Each one of the characters, at least on one side of the culture that you're watching, evolve on the screen in the movie, each one of the characters is experiencing their struggle with greed. And every time that struggle starts showing up on the screen, whether it's De Niro's greed, whether it's DiCaprio's greed, each time one of those characters is starting to put their soul aside for gain and their moral construct aside for gain for profit, that's when the harmonica shows up.

CP: I just want to make sure that I understand. So compared to The Irishman, where the harmonica represented something bad was happening, that was like almost like a warning shot. Whereas in Killers of the Flower Moon, it's all about the greed. I'm curious because there is overlap there, cause mobsters and stuff, they sometimes get greedy.

FY: [smiles] That's exactly the idea. At least that's how I perceived it because when we recorded the tracks, we were trying to create an ambience, an atmosphere [and] I was trying to merge with what the guitar player was playing or [the] bass [player] was playing. And I was just trying to go in and out and leave some space and create this vibe within the construct of the movie and the [knowledge of] the story and how deeply troubling whole thing really is supposed to be.

CP: When you said that this score is based upon conversations and not pictures, did that mean that you didn't get to see any of the film beforehand?

FY: [nods head in agreement]

CP: So did you ever get to see any of the film during the process of this?

FY: No. I was born in France and I had the pleasure of meeting this American woman, we mentioned her early in the conversation, [and] I met her in Cannes during the film festival 25 years ago. And it was very serendipitous to see that this movie, Killers of the Flower Moon, was the big reveal for this particular year.

So we were able to go back to Cannes to celebrate her birthday week, my 50th birthday, [and] the fact that 25 years ago, we had met in that beautiful city, and of course, the fact that this movie was premiering in Cannes. We walked the steps, went to the red carpet, and experienced the whole thing in the most prestigious movie theater of my country along with about 3,500 prestigious people at home [smiles].

It was amazing. It was [a] beautiful experience. However, I have to confess every time the harmonica was coming on the screen, I had a big smile on my face [smiles] — I couldn't really get into the story. So we went back to the premiere in New York (at the NYFF) where I was able to really get into it and really enjoy the process and enjoy the end result.

CP: While you didn't get to see the film while you were making the score, did you do any research with any type of music, whether it be Americana music or another genre?

FY: I did the research early in my career when I was studying the harmonica. Robbie Robertson wanted a harmonica that didn't sound like one. He wanted somebody who could deliver the traditional sound of the harmonica, but also somebody who could sound like a human voice, like a violin, like a guitar, and you hear it when you listen to the soundtrack.

I delivered a wide range of sonics with the same instrument to the point that at some moments, you actually forget you're listening to a harmonica. And that's exactly what you wanted — colors, emotions — so that you can really tap into a different range of emotions.

CP: You've worked with a lot of high-profile artists in your career, from Prince to Stevie Wonder. But I wanted to dive into your relationship with Ed Sheeran. Can you tell me the origins of your relationship and a great memory with him?

FY: Oh my gosh, Ed is the greatest [smiles]. He's extremely generous and simple and down to earth. What amazes me the most [about] him is to watch him switch from being the rock star that he obviously is to being the friend, the little brother that he really is at heart.

Fun fact about Ed: he's a huge Stevie Wonder fan. He's a huge hip hop head. He knows a lot about classic hip hop, like the real hip hop, Black Star, Mos Def-era. He's an amazing talent.

[A] good story about Ed is how we actually met.

We were doing what we call a juke joint. A juke joint is a party we produce with Dave Chappelle and DJ D-Nice. We take a room and lock everybody's cell phones, and it's the greatest party you've never heard of, because everybody's phones are completely locked up.

You have a DJ on one side, you have me and the band on the other, and some of the band members are people I've worked with and [are the] greatest musicians in the world, basically.

Ed heard about the party we were doing in London at the same time as he was selling out Wembley Stadium. And after one of his shows at Wembley, he crashed the party and came to jam with us. And the rest is history.

I think there's a scene of that in a documentary that he released about four years ago. So if you watch the movie again, you'll see Dave and myself in the back [smiles].

CP: I also heard that he was also a surprise guest at one of your shows a couple of months back. How did that come to fruition? Did he just pop up again?

FY: Absolutely [laughs]. He was in New York at the time. He invited me to come to his show when he performed in Washington D.C. at FedExField. So we went to his show and we caught up backstage between the sets.

I told him that I was going to be in New York at the Blue Note Jazz Club. And he said, “Oh, great. I'll be there on Monday.”

And little do you know, he showed up. And it turned out we had a great jam session on stage that night again.

CP: Did you just say you were at the show at FedExField?

FY: Yes. Were you there too?

CP: I was there!

FY: So [do] you remember that particular show [how] he did not have an opening act [and] he opened his own show? We went backstage to catch up with him and chat a little bit, and then went back on stage and did another set. That's the night the jam at the Blue Note was set up.

Killers of the Flower Moon is in theaters now.